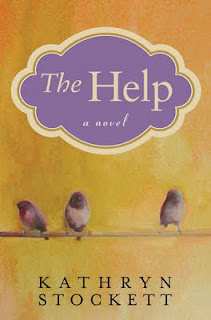

The Help

This book has been making its way around my extended family for several months and just before Thanksgiving break I got my hands on it. Set in Jackson, Mississippi, the book revolves around three women and the racial barriers in the 1960s. The framework for such a classic plot guides you through an awakening of two maids, a young college grad and their community.

After reading it, I passed it along at Thanksgiving dinner and for a brief second before I placed it in my sister-in-law's hands, I felt sad about letting Aibileen, one of the main characters go to someone else.

She cares for her boss' two-year-old little girl as if she were her own and tries to instill an open heart in the nearly doomed child.

From silver patterns to ten different ways to use Crisco, the book interlaces chapters about mundane household chores with others centering on shattering decade-old boundaries. During our own Thanksgiving meal, I fingered the silverware, wondering what pattern my grandmother's silver was. These tiny household details make for an interesting setting as these strong women try to work their way up for air from within the system.

While Kathryn Stockett's first book is not a literary masterpiece, it tells a great story.

An excerpt from the book about Aibileen's job history:

"My first white baby to ever look after was named Alton Carrington Speers. It was 1924 and I'd just turned fifteen years old. Alton was a long, skinny baby with hair fine as silk on a corn…"

"Every window in that filthy house was painted shut on the inside, even though the house was big with a wide green lawn. I knew the air was bad, felt sick myself…"

"When the mama died, six months later," she reads, "of the lung disease, they kept me on to raise Alton until they moved away to Memphis. I loved that baby and he loved me and that's when I knew I was good at making children feel proud of themselves…"

...

Aibileen takes a breath, a swallow of Coke, and reads on. She backtracks to her first job at thirteen, cleaning the Francis the First silver service at the governor's mansion. She reads how on her first morning, she made a mistake on the chart where you filled in the number of pieces so they'd know you hadn't stolen anything.

"I come home that morning, after I been fired, and stood outside my house with my new work shoes on. The shoes my mama paid a month's worth a light bill for. I guess that's when I understood what shame was and the color of it too. Shame ain't black, like dirt, like I always thought it was. Shame be the color of a new white uniform your mother ironed all night to pay for, white without a smudge or a speck a work-dirt on it."

"My first white baby to ever look after was named Alton Carrington Speers. It was 1924 and I'd just turned fifteen years old. Alton was a long, skinny baby with hair fine as silk on a corn…"

"Every window in that filthy house was painted shut on the inside, even though the house was big with a wide green lawn. I knew the air was bad, felt sick myself…"

"When the mama died, six months later," she reads, "of the lung disease, they kept me on to raise Alton until they moved away to Memphis. I loved that baby and he loved me and that's when I knew I was good at making children feel proud of themselves…"

...

Aibileen takes a breath, a swallow of Coke, and reads on. She backtracks to her first job at thirteen, cleaning the Francis the First silver service at the governor's mansion. She reads how on her first morning, she made a mistake on the chart where you filled in the number of pieces so they'd know you hadn't stolen anything.

"I come home that morning, after I been fired, and stood outside my house with my new work shoes on. The shoes my mama paid a month's worth a light bill for. I guess that's when I understood what shame was and the color of it too. Shame ain't black, like dirt, like I always thought it was. Shame be the color of a new white uniform your mother ironed all night to pay for, white without a smudge or a speck a work-dirt on it."

...

"…so I go on and get the chiffarobe straightened out and before I know it, that little white boy done cut his fingers clean off in that window fan I asked her to take out ten times. I never seen that much red come out a person and I grab the boy, I grab them four fingers. Tote him to the colored hospital cause I didn't know where the white one was. But when I got there, a colored man stop me and say, Is this boy white?"

"…so I go on and get the chiffarobe straightened out and before I know it, that little white boy done cut his fingers clean off in that window fan I asked her to take out ten times. I never seen that much red come out a person and I grab the boy, I grab them four fingers. Tote him to the colored hospital cause I didn't know where the white one was. But when I got there, a colored man stop me and say, Is this boy white?"

"And I say, Yessuh, and he say, Is them his white fingers? And I say, Yessuh, and he say, Well, you better tell em he your high yellow cause that colored doctor won't operate on a white boy in a Negro hospital. And then a white policeman grab me and he say, Now you look a here-"

Comments